The Biology of Grief: How the Brain Responds to Loss and What It Means for Mental Health Treatment

The Biology of Grief: How the Brain Responds to Loss and What It Means for Mental Health Treatment

By Anna Guerdjikova, PhD, LISW, CCRC, Director of Administrative Services, Harold C. Schott Foundation Eating Disorders Program, Lindner Center of Hope

By Anna Guerdjikova, PhD, LISW, CCRC, Director of Administrative Services, Harold C. Schott Foundation Eating Disorders Program, Lindner Center of Hope

Grief is one of the most universal human experiences, yet it remains deeply personal and often misunderstood. Many people ask: Why does grief feel like physical pain? Why can’t I think clearly while grieving? Can grief actually change the brain?

Modern neuroscience shows that grief is not just emotional—it is also biological. The brain processes grief using circuits tied to pain, memory, attachment, and even reward. Understanding the biology of grief not only validates the intensity of loss but also points toward new treatments for conditions like Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD).

What Happens in the Brain During Grief?

Grief is a complex neurobiological process that activates many of the same brain regions involved in both physical pain and reward. Imaging studies reveal that grief is not just a “feeling”—it is a whole-brain response that affects emotion, cognition, and physical health.

The Pain of Loss and the Anterior Cingulate Cortex

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which regulates emotions and pain, becomes highly active during acute grief. This explains why the loss of a loved one feels like literal pain. The term “broken heart syndrome” is not just a metaphor—your brain processes the pain of loss through the same pathways as physical pain.

Why Grief Feels Like Fear, Anxiety, and Yearning

The Amygdala and Fear Response

The amygdala, the brain’s emotional alarm system, becomes overactive in grief. This can lead to heightened anxiety, mood swings, hypervigilance, and sleep problems—symptoms many grieving people recognize.

Reward Pathways and Longing

Regions like the nucleus accumbens, part of the brain’s reward system, continue to “search” for the person who is gone. This explains the intense yearning that many feel, such as “seeing” a loved one in a crowd or feeling their presence. The brain essentially craves an emotional “fix” that is no longer available.

Brain Fog and Cognitive Changes in Grief

During grief, many people describe “grief brain” or brain fog—difficulty concentrating, forgetfulness, and impaired decision-making. This is linked to reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for focus, planning, and executive function. As the brain allocates energy to processing emotion, cognitive clarity temporarily suffers.

When Grief Becomes Prolonged (Prolonged Grief Disorder)

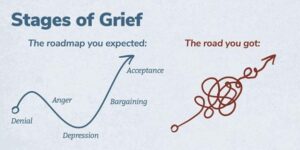

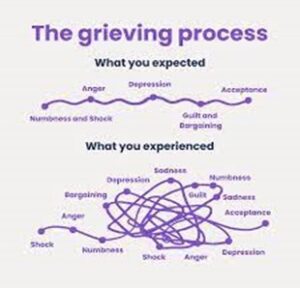

For most people, grief becomes less intense with time. But in some, grief remains persistent and debilitating—now recognized as Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD).

In PGD, the brain’s reward and attachment circuits remain highly active, as if the brain cannot fully accept the permanence of loss. This “stuck” biological response reinforces yearning and prevents healing. Recognizing PGD as a neurobiological condition—rather than a sign of weakness—validates patient experience and guides more targeted treatment.

How Neuroscience Informs Grief Treatment

Understanding the brain’s role in grief has practical implications for treatment and recovery.

Targeted Psychotherapy

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for grief and Complicated Grief Therapy (CGT) help retrain maladaptive thought patterns and regulate emotional circuits.

- Mindfulness-based therapies calm the amygdala and strengthen the prefrontal cortex, reducing anxiety and improving focus.

Pharmacological Interventions

- Antidepressants may help when grief co-occurs with major depression, but they are often less effective for PGD, which is distinct from depression.

- Research is exploring medications that target the brain’s reward and attachment pathways to help “unstick” prolonged grief.

Neurofeedback and Brain Stimulation

- Neurofeedback trains individuals to regulate brain activity.

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), already used for depression, is being studied as a tool to modulate brain regions involved in grief.

While these treatments are emerging, they reflect the growing field of neuroscience-driven grief care.

Moving Toward Compassionate, Science-Informed Care

Grief is not only an emotional journey—it is a biological one. By understanding how the grieving brain works, patients and families can better appreciate the physical reality of loss, and clinicians can offer more compassionate and effective care.

Recognizing grief as a brain-based process helps reduce stigma, validates the lived experience of mourners, and opens the door to holistic, neuroscience-informed treatments. For those struggling with loss, this knowledge can bring comfort: grief is not a weakness—it is a natural biological response, and healing is possible.

The biology of grief shows us that loss profoundly affects the brain—triggering pain, fear, yearning, and cognitive fog. But it also shows us that treatment is possible. By combining neuroscience insights with compassionate mental health care, patients, families, and clinicians can work together to move through grief toward healing.