Coregulation

by Dawn Anderson, LPCCS

Humans are a very resilient species. We have overcome generations of burdens to accomplish family unity, and yet this effort renews with new barriers and challenges each year. A vital component of a thriving family unit is the ability to co-regulate. Co-regulation describes the process in which a parent can identify their child’s need for help, recognize their own emotional reaction, and then help themselves cope to share that gift with their child.

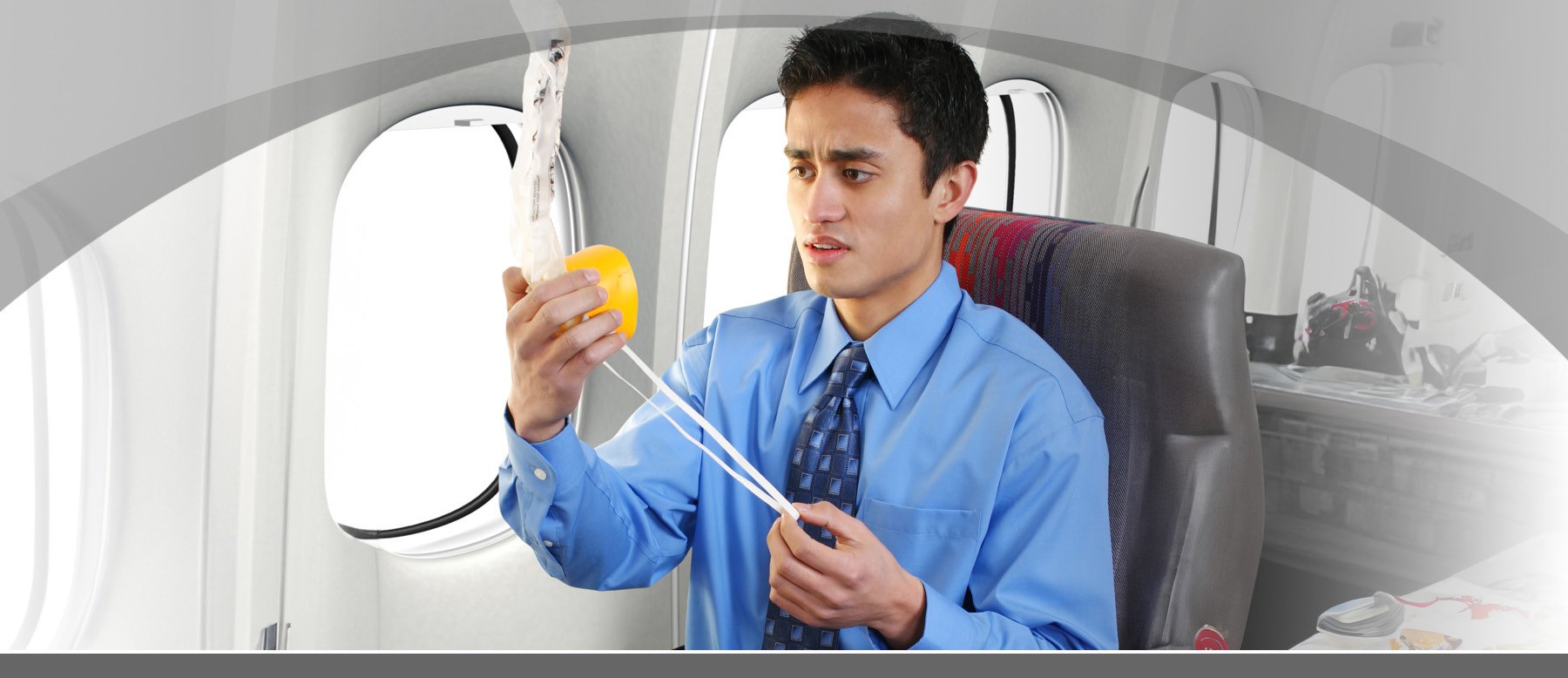

Just like the airplane metaphor- you must put on your own oxygen mask before you can help others. As a parent, we are bombarded with requests for our time, resources, and attention. We have a certain amount of emotional energy in the day, and this is a renewable resource! Taking the time to take care of your own emotional health allows you to be more responsive in the ways we’d like to show up with our children. Another huge burden on parents is the one we place there ourselves- guilt. We fret about the choices to be made, the amount we’re able to give our children, and the perpetual feeling we aren’t enough. The reality is we all bring different types and amounts of skills and talents to the table.

Some of us have different capacities for stress, and that doesn’t make us good or bad. Sometimes it’s helpful to think of your stress tolerance as a cup- is yours a 12 oz picnic cup? A 2 oz bathroom water cup? An Olympic swimming pool? Whatever the size, we must take ownership of knowing where we are throughout the day, and how we are showing up in interactions with our children. We also need to be intentional about emptying said cup proactively throughout the day, so it doesn’t overflow. Overflow here is where we see the unintentional screaming at our precious ones, storming off, or being unable to play with them after our long day.

Lastly in explanation, its valuable to consider the way language impacts our thoughts, feelings, and behavior. In common language, we say things about children such as “they’re a mess,” “they’re not listening to me,” “they’re being a brat.” In all humans, we have a system in our brain that takes in information and decides if it’s safe or not, and then sends it to either the thinking part or the survival part of our brain. What our brains decide as safe depends on the person. Some of us have different themes that activate the threat systems in our own bodies, and with careful observation, you might be able to pin these down for your loved ones. If this feels difficult, a licensed clinical therapist can help.

Once the “threat center” of your brain decides something isn’t safe, we have survival reactions: our heart rate picks up, heavy breathing, we feel shaky, and/or we have a hard time thinking clearly due to the process where your brain diverts power from the thinking brain to the survival brain. That said, that’s part of why it’s hard to talk to someone who doesn’t feel safe. It’s hard for them to hear you, and hard for them to express how they feel in words. If we use compassionate language, it removes blame from the driver seat. Try “they look like they need help” or “they are having some big feelings” You and your child are a team, and teams are stronger when they work from the operating point that we win when we work together with our strengths.

That said, here are some helpful tips to regulate with your child:

- When you identify that your child needs help, first check in with yourself on what you need to be best able to respond to them. Its valuable to practice the breathing skills when you don’t need them, so you can use them in the moment when you do. Trying to only use them in a moment of crisis is like expecting yourself to learn to swim in the choppy ocean.

- Get on their level. Kneel, squat, or sit down if necessary. Looking up at someone activates the “threat” center of our brain and makes it harder to calm down.

- Use a low, consistent tone. If I want someone to hear me, I need to be quieter, not louder. Especially if they are yelling. Keep your messages concise and direct, such as “I want to hear you, and it’s easier when you’re at a level 2” or “Let’s take a deep breath together then we can put your toy back together.”

- Take a full, deep breath in your nose and exhale slowly out your mouth. Imagine feeling like you’re smelling something super pleasant and trying to cool off hot cocoa with the exhale. Even if they are not in the place to participate because they’re too dysregulated, their body will unconsciously mirror yours.

- If you’re not able to offer your child 1:1 proximity, or their bodies are not safe for you (i.e. hitting) consider regulating in the room by counting items together. Redirection is a powerful tool for the right moment. Again, a licensed therapist can help you catch these windows of opportunity.

- If appropriate, leave the room and regulate yourself before returning. Use your words to announce the intention “I need two minutes to regulate myself and I will be back to work on this with you.” Stepping away from the situation is a tool that can give teenage parents the break we need to not ground our child for the next 100 years when we’re both stuck in an argument.

- With any strategy, it’s important to come back together and process Use the compliment sandwich: Identify one thing that went well, offer constructive feedback, and close with another positive thing you noticed or future oriented reconnection point. “I’m proud of you for breathing with me. Next time, do you think it would help if we used the feelings chart? I’m glad I have you.”