Category: Blog

By Michael O’Hearn, MSW, LISW-S

The drum is one of the oldest musical instruments. An interesting paradox of medical and cognitive neuroscience is how a range of intra- and inter-personal stress mediation, self-regulation, and mind-body continuity interventions are accomplished through ancient

traditions of meditation (mental training) (Davidson & McEwen, 2012; Khalsa, Rudrauf, Davidson, & Tranel, 2015), and drumming (Bittman, Berk, Fleton, Westenguard, Pappas, & Ninehouser, 2001; Bittman, Berk, Shannon, Sharaf, Westenguard, Guegler, & Ruff, 20015; Bittman, Croft, Brinker, van Laar, Vernalis, & Elisworth, 2013).

This paper outlines a drumming technology that naturally integrates with Shamatha (Object) meditation (Ponlop, 2006). Drumming technology is a source of practically limitless transverse, bi-lateral, fine, and gross motor algorithms for individuals, couples, or groups. The targeted and individualized interventions (algorithms) serve as the object of Shamatha meditation. The psychoneuromuscular (PNM) practice not only conditions self-regulation, mind-body continuity, and stress mediation; the acquired abilities are eventually habituated in procedural or working memory (Sacks, 2007; Sapolsky, 2017) in

client systems.

The proposed drumming technology is central to a theoretical paper on music-based learning culture in former totalitarian undergraduate, graduate, and post-graduate education. It is expected to be published by Summer, 2018. Michael Radin, Ph.D., a classically trained pianist and Mathematics Professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology and Riga Technical University, and Liga Engele, Head of the Music Therapy

Center at Leipaja University, Latvia are lead and co-authors.

A Drumming Technology

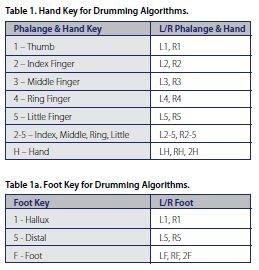

The following is a description of drumming technology components and processes, some dyadic tables, and a low complexity algorithm. Table 1 and 1a outline phalange/hand, and foot sources for drumming algorithms:

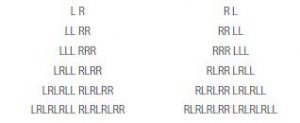

Time Signatures. Time signatures are expressed as fractions; Table 2 illustrates a 4/4-time signature. The denominator represents the total number of beats per measure; the numerator represents the number of beats played per measure. Any source combinations can fit with practically any desired time signature.

Additional time signatures are not limited to 3/3, 3/4, 2/4, and 6/8.

Basic Rhythms. The following are basic rhythmic patterns ubiquitous in drumming and dance choreography. Again, any combination of sources can fit these basic rhythms.

Accents. Downbeat and syncopation are two examples of various accents to basic rhythms. Table 2 also illustrates the downbeat accent in 4/4 time.

Syncopated rhythms have accents that are not necessarily patterned or predictable; the accent often “anticipates,” or is played on the half-beat in Latin rhythms, Jazz, and progressive rock music. As syncopated rhythms require additional effort and resources to capture and integrate, they are indicated to enhance integration in trauma recovery (van der Kolk, 2009; 2014) patients.

Medium. Drum kit, hand drum, finger drum, homemade drum, lap, belly, table, or other are examples of medium – the instrument selected for a drumming algorithm.

Tuplet. Tuplet is the number of strokes attributed to each beat (the numerator) in any time signature; typically, single, double, or triple.

Tempo. A metronome is a meter that measures tempo in beats per minute/second (bpm/s), and provides an auditory “click track.” The practitioner plays at a precise tempo, in sync or “on meter” with the metronome. There are advantages to fast and slow tempo. Drumming algorithms can emphasize one, the other, or include both.

Duration. Duration is the length of time of practice session, or the number of repetitions a drumming algorithm is played.

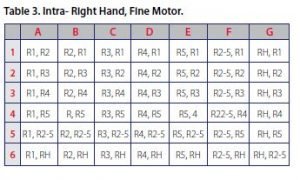

Examples of Dyadic Tables and a Drumming Algorithm.

The following are samples of fine and gross motor, transverse and bi-lateral dyadic tables for drumming algorithms. It is followed by an illustration of a low complexity drummingalgorithm.

SUMMARY

Meditative drumming is a psychoneuromuscular (PNM) intervention for individuals, couples, and groups that facilitates self-regulation, mind-body continuity, and stress reduction.

Individualized drumming algorithms are designed to engage one or a combination of: autonomic/vagal, cognitive, emotional, language, visual-spatial, fine/gross motor, and memory along transverse and/or bi-lateral pathways. Acquired abilities from meditative drumming algorithms are eventually habituated in procedural or working memory (Sacks, 2007; Sapolsky, 2017).

Its value for generating nonlinear efficacy in all settings (including all levels of care continuums), is matched only by its portability and cost efficiency.

REFERENCES

Davidson, R. & McEwen, B. (2012). Social influences on neural plasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being.

Nature Neuroscience, 689-695.

Khalsa, Rudrauf, Davidson, & Tranel. (2015). The effect of meditation on regulation of internal body states. Frontiers in Psychology, 1-15.

Bittman, B., Berk, L., Felten, D., Westenguard, J., Pappas, J., Ninehouser, M. (2001). Composite effects of group drumming music therapy on modulation of neuroendocrine-immune parameters in normal subjects, Alternative Therapies In Health and Medicine, Jan: 7(1), 38-47.

Bittman, B., Berk, L., Shannon, M., Sharaf, M., Westenguard, J.,

Guegler, K., Ruff, D. (2005). Recreational music-making

modulates the human stress response: a preliminary

individualized gene expression strategy, Medical Science

Monitor, 11, BR31-40.

Bittman, B., Croft, D., Brinker, J., van Laar, R., Vernalis, M., & Elisworth,

D. (2013 Recreational music-making alters gene expression pathways in patients with coronary artery disease, Medical Science Monitor,19, 139-147.

Ponlop, D. (2006). Mind beyond death. Ithaca, NY: Snowlion.

Sacks, O. (2007). Musicophilia. NY: Vintage.

Sapolsky, R. (2017). Behave: The biology of humans at our best and worst. NY: Penguin.

van der Kolk, B. (2009). Presentation of Trauma and Recovery, to the Milton H. Erikson Foundation Evolution of Psychotherapy Conference, Sacramento, CA.

van der Kolk, B. (2014). Trauma Recovery presentation to the 2014 International Trauma Conference, Boston, MA.